My Mirror column:

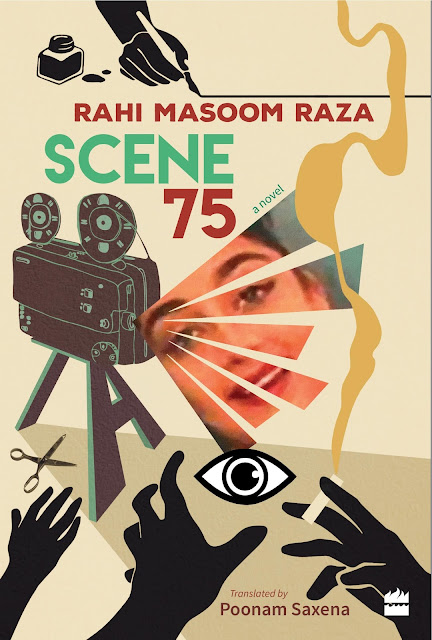

Rahi Masoom Raza's biting 1977 novel Scene 75 is a brutally frank and funny account of the Bombay film industry -- and of our need to tell stories.

Four decades after it was first published, Rahi Masoom Raza's marvellous novel Scene 75 – just out in Poonam Saxena's pacy new English translation – can still plunge us headlong into the hectic, gossipy universe of Bombay filmdom. Raza's prose has the infectious quality of the born raconteur, somehow managing to combine circuitous, detailed backstories with new characters introduced -- and parted from -- at breakneck speed.

But unlike say, Ismat Chughtai's Ajeeb Aadmi -- a rather thinly disguised version of the unhappy Guru Dutt-Geeta Dutt-Waheeda Rehman triangle -- Raza does not place us at what we might think of the centre of the action. Yes, big names are dropped with elan, but it is not their lives that Scene 75 wants us to enter.

Real-life stars, producers, character actors, from Asha Parekh and Sanjeev Kumar to David and Manmohan Krishna, only provide the matrix of instant credibility for Raza's fictional protagonists, who are people on the fringes of the industry: aspiring screenwriters, starlets on the make, housewives desperate to wrangle film premiere invitations.

This is the seamy underbelly of Bollywood, fed on crumbs dropped by the rich and famous. Sometimes these crumbs are literal, like the supposedly jinxed royal bed from the set of a film called Adle-Jahangir that becomes the centrepiece of the flat shared by the book's four struggling friends -- or the transparent nightie deemed too small for Hema Malini that makes its way to Radhika, wife of the failing screenwriter Phandaji, and practically changes her life.

More often, though, they are tidbits of information that offer access to the filmi duniya. Scene 75 derives much of its juiciness from the interactions between various classes of hangers-on, who have different degrees of this access, and most of whom are pretending to have more than they actually do. So, for instance, we have the grave, revolutionary VD acquiring new skills of deception when it comes to showing a young Anglo-Indian woman called Rosy dreams of a future as heroine: 'Today BR Chopra made a pukka commitment to give you a break in his next film. And Nasir Husain said, “Bring her over right now, I want to sign her for my next film.” But he makes such escapist films. I won't let you work there...' VD's friends – particularly the book's central protagonist Ali Amjad, who seems partly modelled on Raza himself -- are upset with his bald-faced lies. 'Why are you showing the poor thing these false dreams?' Ali Amjad demands to know. VD's answer is a counterquestion that really has no answer: 'But why does she see them?'

Why does she, indeed? Scene 75, especially as it moves towards its tragic denouement, emerges as a book full of cynical truths, truths which it would be unfair to describe as takedowns because they don't seem to contain malice (even when, as with the book's many lesbian characters, they bear the burden of prejudice).

But even as Raza's humour transitions from dark to pitch black, and his heroes mock themselves for their loss of idealism, I had the impression that Raza could not entirely condemn his fantasising characters. Because he understood their need for fiction.

That need for fiction appears over and over again in the book – whether in Bholanath Khatak's desire to make his wife Rama dress like Waheeda, or in journalist Pancharan Mishra turning of the cook-turned-screenwriter Ramnath into Ramanathan, complete with a detailed life-story.

“Because of his father's sudden death, Ramanathan had been unable to take his MA exam. The memory of his university days still filled Ramanathan with sadness. The glory of those tennis lawns, the revelries of the drama club...” “Everyone knew it was lies,” writes Raza. “But everyone had had similar things written about them, so no one bothered to check the truth.”

Earlier in the book, we encounter the wonderful Mai's Adda, where everyone from Sahir Ludhianvi to Raj Kapoor had drunk alcohol and eaten fried fish on credit. Fiction here runs like a rich vein through fact; if you cut off the supply of make-believe, it might kill us.

“Whenever one of her debtors became famous, Mai would hang his photograph in her adda and talk about him as if he were her own son...” When D'Souza buys up Mai's Adda, he lets Mai masquerade as if she is still the actual owner. Then when the real Mai dies, people can't quite adjust to life without a Mai -- so they begin to call Mrs. D'Souza 'Mai'. That desperate desire to keep up appearances is also at the crux of Ali Amjad's titular Scene 75, in which a character called Abulkhair's mother is dictating a letter to a munshi at a streetcorner. “Everyone is unwell. Why are you making me say that everything is all right?” says the munshi.

This then, might be the truth at the heart of Scene 75, and perhaps Raza's comment on our cinematic fantasies: When is a lie not simply a lie? When it's what we need to believe to live.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 4 Feb 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment