This week's Mirror column:

Farah Khan's Happy New Year rides on her usual tweaking of Hindi film history, only with a dash of low level slapstick humour.

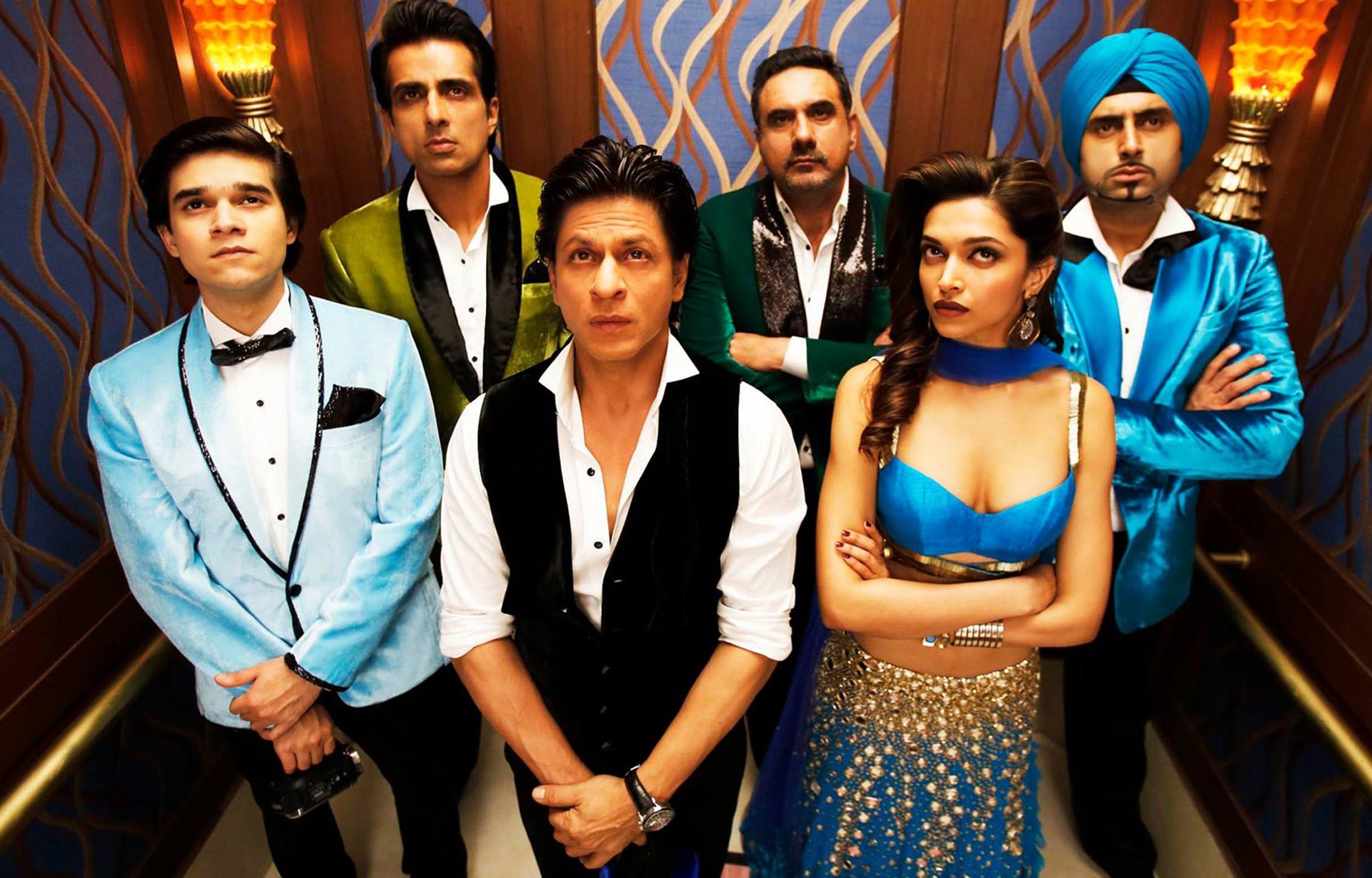

Coming from a director so obsessed with sculpted bodies, Farah Khan's Happy New Year is surprisingly flabby. It's ostensibly a heist film, where Charlie (Shah Rukh Khan) and his ragtag bunch -- a deaf ex-army bomber (Sonu Sood), an expert safecracker (Boman Irani), a youthful hacker (Vivaan Shah) and a ghati lookalike of the villain's suave son (Abhishek Bachchan) -- are out to rob expat millionaire Charan Grover (Jackie Shroff) of the world's most expensive diamonds. But, it turns out, all this is only to avenge the framing of Charlie's honest father -- and a perfectly fun heist gets padded out with enough weepy declarations to make a giant sponge. If these mile-long intros for each annoying character weren't enough to make you wring your hands (and feel like wringing their necks), the gang decides its best form of cover is to show up as competitors in a dance championship, and a bar dancer called Mohini (Deepika Padukone) is hired to turn this worse-than-Full-Monty group into a national team.

The film reprises every trick in Farah Khan's book, some in double dose. So there's not one but two sets of abdominal muscles on gleaming display (Sonu Sood gives Shah Rukh competition). Abhishek Bachchan compensates for the absence of a six-pack by offering us two of himself for the price of one. (He's not bad at being funny, but it's a pity that Farah serves him up with a large dollop of gross-out-loud humour of the kind usually associated with Rohit Shetty and Sajid Khan (Farah's brother). And finally, of course, there's the director's well-known penchant for making every second scene play a double role -- as itself in the present, and as the ghost of some iconic Hindi movie moment in the past. So we have prize fighter SRK, asked why he tolerates being beaten up, answering, "Kaun kambakht bardaasht karne ke liye pitta hai." Our hero explodes when he hears "Tera baap chor thha" echoing in his head. Grover's firm is called Shalimar Securities, and RD Burman's 'Mera Pyar, Shalimar' soundtrack rings out every time bachelor Boman encounters the topsecret safe. Deepika's 'entry' is via an expectant crowd shouting 'Mohini, Mohini', catapulting us into memories of Tezaab (1988), where Madhuri Dixit played the hapless Mohini, forced to dance by her drunkard father to pay off his many debts. Later, Deepika's speech as a dance coach is a repeat of Shah Rukh's hockey coach act in Chak De India. The list goes on; Khan is clearly indefatigable when it comes to piling on the references. But one dearly wishes her Hindi movie homage amounted to more than a series of knowing winks.

To be fair, there are a few other things going on the film, things that can't be explained as part of Hindi movie pastiche. First, this is a Shah Rukh Khan film in which SRK refuses to romance the girl - leaving the girl to romance him. (Leading to a running visual gag I most enjoyed - every time Mohini touches Charlie, sparks fly - literally. Flames leap up, shirts catch fire.) Second, though Sonu Sood tries to convince Mohini that Charlie's refusal to turn the charm tap on is because he doesn't know how to talk to women, it's clear that Charlie can't imagine Mohini as a love interest because he's such a smooth-talking English-vinglish type and she's just a sadakchhap bar dancer.

As soon as Charlie (once Chandramohan Manohar Sharma, but now "naam bhi English") lets loose his stream of fluent English, the Marathispeaking Mohini arrives to luxuriate in it. Khan's use of English as what turns Mohini on is clearly drawn from another heist comedy, A Fish Called Wanda. But while Jamie Lee Curtis being seduced by the sound of Italian (and later Russian) played only on some stereotype about sexy European-ness, the non-English speaker being seduced by English is a devilishly fun take on cross-class desire in India.

I was disturbed, however, by the film's continual dwelling on Mohini's work as a bar dancer making her a "cheap" "bazaaru aurat", with Charlie feeling no compunction either about making these judgements, or delivering completely unconvincing apologies to Mohini when she overhears him. Khan has no qualms about buying into the patriarchal mindset that creates and condemns the "chhamiya" -- nor any about co-opting this condemned cultural form into a saleable commodity called "Chhamiya style".

Perhaps that's because anything goes in pursuit of a win, especially a win for India on international soil. HNY purports to be a film about winners and losers, but how is loser-ness defined? By the lack of money (for most of them), the lack of English (for Deepika), and in the case of our hacker boy, the lack of girls falling all over him. But at least they all had integrity. And who are our winners? A team which hacks, blackmails and essentially cheats its way into the dance championship finals, finally winning by emotional manipulation of the audience.

Farah Khan's Happy New Year rides on her usual tweaking of Hindi film history, only with a dash of low level slapstick humour.

Coming from a director so obsessed with sculpted bodies, Farah Khan's Happy New Year is surprisingly flabby. It's ostensibly a heist film, where Charlie (Shah Rukh Khan) and his ragtag bunch -- a deaf ex-army bomber (Sonu Sood), an expert safecracker (Boman Irani), a youthful hacker (Vivaan Shah) and a ghati lookalike of the villain's suave son (Abhishek Bachchan) -- are out to rob expat millionaire Charan Grover (Jackie Shroff) of the world's most expensive diamonds. But, it turns out, all this is only to avenge the framing of Charlie's honest father -- and a perfectly fun heist gets padded out with enough weepy declarations to make a giant sponge. If these mile-long intros for each annoying character weren't enough to make you wring your hands (and feel like wringing their necks), the gang decides its best form of cover is to show up as competitors in a dance championship, and a bar dancer called Mohini (Deepika Padukone) is hired to turn this worse-than-Full-Monty group into a national team.

The film reprises every trick in Farah Khan's book, some in double dose. So there's not one but two sets of abdominal muscles on gleaming display (Sonu Sood gives Shah Rukh competition). Abhishek Bachchan compensates for the absence of a six-pack by offering us two of himself for the price of one. (He's not bad at being funny, but it's a pity that Farah serves him up with a large dollop of gross-out-loud humour of the kind usually associated with Rohit Shetty and Sajid Khan (Farah's brother). And finally, of course, there's the director's well-known penchant for making every second scene play a double role -- as itself in the present, and as the ghost of some iconic Hindi movie moment in the past. So we have prize fighter SRK, asked why he tolerates being beaten up, answering, "Kaun kambakht bardaasht karne ke liye pitta hai." Our hero explodes when he hears "Tera baap chor thha" echoing in his head. Grover's firm is called Shalimar Securities, and RD Burman's 'Mera Pyar, Shalimar' soundtrack rings out every time bachelor Boman encounters the topsecret safe. Deepika's 'entry' is via an expectant crowd shouting 'Mohini, Mohini', catapulting us into memories of Tezaab (1988), where Madhuri Dixit played the hapless Mohini, forced to dance by her drunkard father to pay off his many debts. Later, Deepika's speech as a dance coach is a repeat of Shah Rukh's hockey coach act in Chak De India. The list goes on; Khan is clearly indefatigable when it comes to piling on the references. But one dearly wishes her Hindi movie homage amounted to more than a series of knowing winks.

To be fair, there are a few other things going on the film, things that can't be explained as part of Hindi movie pastiche. First, this is a Shah Rukh Khan film in which SRK refuses to romance the girl - leaving the girl to romance him. (Leading to a running visual gag I most enjoyed - every time Mohini touches Charlie, sparks fly - literally. Flames leap up, shirts catch fire.) Second, though Sonu Sood tries to convince Mohini that Charlie's refusal to turn the charm tap on is because he doesn't know how to talk to women, it's clear that Charlie can't imagine Mohini as a love interest because he's such a smooth-talking English-vinglish type and she's just a sadakchhap bar dancer.

As soon as Charlie (once Chandramohan Manohar Sharma, but now "naam bhi English") lets loose his stream of fluent English, the Marathispeaking Mohini arrives to luxuriate in it. Khan's use of English as what turns Mohini on is clearly drawn from another heist comedy, A Fish Called Wanda. But while Jamie Lee Curtis being seduced by the sound of Italian (and later Russian) played only on some stereotype about sexy European-ness, the non-English speaker being seduced by English is a devilishly fun take on cross-class desire in India.

I was disturbed, however, by the film's continual dwelling on Mohini's work as a bar dancer making her a "cheap" "bazaaru aurat", with Charlie feeling no compunction either about making these judgements, or delivering completely unconvincing apologies to Mohini when she overhears him. Khan has no qualms about buying into the patriarchal mindset that creates and condemns the "chhamiya" -- nor any about co-opting this condemned cultural form into a saleable commodity called "Chhamiya style".

Perhaps that's because anything goes in pursuit of a win, especially a win for India on international soil. HNY purports to be a film about winners and losers, but how is loser-ness defined? By the lack of money (for most of them), the lack of English (for Deepika), and in the case of our hacker boy, the lack of girls falling all over him. But at least they all had integrity. And who are our winners? A team which hacks, blackmails and essentially cheats its way into the dance championship finals, finally winning by emotional manipulation of the audience.